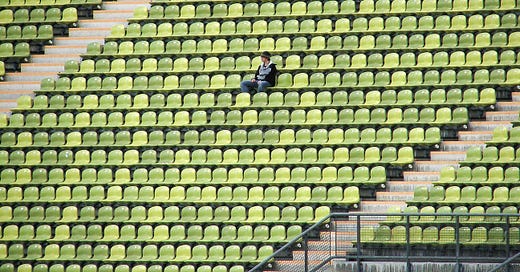

Did I just travel back in time to 2020 and the era of Covid-19 sports bubbles?

It felt that way when tuning into the Tottenham Hotspur vs. Leicester City WSL game last Sunday.

There were no crowds to be seen in the stands.

The game was showing on the BBC. And for anyone not from the UK, that is a big deal.

In the UK, we have a few options for watching WSL games:

Sky Sports — a pricey sports subscription service — gets the rights to show two WSL games per week.

BBC — a national broadcaster — gets the rights to show one.

And FA Player/YouTube shows the remaining games.

Being on the BBC is a huge opportunity for teams, and the WSL, because it has the potential to tap into completely different audiences — those who might not naturally seek out women’s football.

Unfortunately Tottenham Hotspur didn’t take advantage of this opportunity. The way the cameras were positioned throughout the game made it look as though the two teams were playing to an empty stadium.

That wasn’t true. There were 1,314 fans enthusiastically hollering throughout the game. But for anyone tuning in on the BBC, it looked as though there were 10 fans in attendance and social distancing protocols were back.

It’s a markedly different experience to what casual BBC viewers would get if they tuned into a today’s game where Chelsea played Arsenal to a crowd of over 30,000 at Stamford Bridge.

Some forward planning around how the Tottenham Hotspur’s game was filmed or how the crowd were seated could have created more of an engaging atmosphere on TV.

Still there’s only so much teams and leagues can do with existing infrastructure. It’s not easy, nor quick, to build new grounds and facilities.

Women’s sports are stuck with a Goldilocks problem where stadiums are either too big or too small. Nothing fits just right.

Women’s teams have two options. They can either lean on stadiums built for men’s teams, which are great for being centrally located and have top-class facilities. But they also come with challenges such as scheduling clashes with the men’s team, sometimes being too large for certain women’s teams, and women’s teams never being able to fully put their own stamp on the stadium.

Plus, if a club is directly linked to a men’s team, like most UK teams are, they are often at the mercy of the club’s ownership who may not always see the value in women’s football. A Bloomberg report this week shows how some men’s clubs are concerned about the financially viability of having women’s professional teams.

“In England, with the women’s league, I believe if you gave some owners the opportunity to back out of supporting the women’s game, I think they think they would, simply because I feel like they’re all about profit and right now, they’re losing money with the women’s game,” said football pundit Ian Wright in the Bloomberg article. “And let’s be honest, not all clubs actually believe in what we are trying to do. For some of them this is just a box to tick.”

On the other hand, women’s teams can leverage training grounds, which are much smaller but also tend to be located in hard to access areas (not ideal for growing the game), don’t have top-tier facilities, and don’t provide the same game day experience to fans as at a top-class stadium.

Brighton is tackling this problem by building its own purpose-built stadium — a proposal which was signed in 2023 and likely won’t be completed till 2027/2028.

What will the WPLL, the organisation in charge of the WSL and Women’s Championship, do in the mean time?

Could it learn from across the pond and explore a made-for-TV format of the likes 3x3 basketball league Unrivaled is successfully pulling off?

I love how Unrivaled’s stadium sits within a production studio in Miami and is designed with the TV viewer in mind. The creators recognized that since all games were hosted in Miami that the opportunity for repeat ticket revenue was limited and instead prioritized TV audiences.

While it’s a really smart model for Unrivaled, I am not sure it could translate to the WSL. The game day experience has been vital for the WSL’s growth. A trip to women’s football game can be more family friendly, lighthearted, and cost effective than the men’s game. At the same time, there isn’t the same consistency in the women’s league game day experience compared to the men’s. The stadiums and the crowds they draw play a big role in that. WSL teams with huge budgets and resources, such as Arsenal and Chelsea, pull off unparalleled game days.

The USA is facing its own goldilocks problem in the NWSL.

The one advantage the NWSL has is its already built CPKC Stadium, home to NWSL team Kansas City Current. It’s the first purpose-built women’s professional sports stadium in the world and opened last year. It’s providing a roadmap for what is possible. Designed by women-led firm Generator Studio, the 11,500-seat stadium located downtown has been home to sellout games throughout the 2024 NWSL season.

As The Equalizer points out, since CPKC Stadium is the one venue that is owned outright by the NWSL it can be helpful for scheduling major events like the NWSL Championship because it is not at the mercy of scheduling clashes where multiple teams are sharing one stadium. This is frequently an issue in the WSL where the largest stadiums are often shared with the men’s teams who play around the same time of the year.

Yet CPKC only has a capacity of 11,500 which is probably enough for the US market at the moment, but what about in the future? It certainly wouldn’t be the right size for the UK market for championship events. The 2024 FA Women’s Cup final had an attendance of 76,082 and took place at Wembley Stadium.

Plus, building a new stadium comes with its own set of challenges. The costs for building CPKC increased during the building process. And the renovations of the abandoned White Stadium, which is set to be the home for NWSL team BOS Nation FC, has doubled in projected costs to over $200 million causing controversy amongst Boston tax payers.

It’s hard to justify building new stadiums for women’s teams when budgets are already tight, but at the same time how will revenues grow without having top-tier centrally-located venues. Again, we hit the Goldilocks problem.

It doesn’t feel like there will ever be an easy solution. What does seem clear is that CPKC stadium is just right for most of the time (Excluding major events or championships.) And maybe that’s where we need to start rather than continue to delay in making infrastructure investments in women’s sports.

It’s exciting to see some momentum starting to build with CPKC and Brighton. Even this summer work will begin on a $78 million sports performance center for the WNBA team Indiana Fever. In this center, players will have access to two regulation-sized courts, strength and conditioning equipment, spa-like facilities — such as sauna, massage, infrared light therapy — as well as childcare facilities, hair and nail salon, and a production studio.

The best of the rest

This is an interesting one. The LPGA has cancelled an upcoming event because of financial neglect from the event’s underwriter. What’s shocking is that the event underwriter failed to make any payments for both 2024 and 2025 events. I doubt it will be long till before we find out who the underwriter is.

The Football Association is floating a proposal that would allow B teams, which are football clubs’ development teams, to play in the Women’s National League, which is the league that sits below the WSL and the Women’s Championship.

The proposals are part of a strategy aimed at “narrowing the gap from youth to senior football,” with top-tier clubs having provided feedback to the FA that they “feel the competition for their academy teams does not challenge players enough to develop them for their first teams and beyond.”

The WNBA breaks down free agency ahead of the draft.

Shenzhen will host the Billie Jean King Cup Finals for the next three years.

USA Today’s Nancy Armour on women’s sports “told you so” moment.

Football star Lauren Holiday talks about how the NWSL has an edge over the WSL in competitiveness and her experience joining the board of Mercury/13, a pure play investor in women’s football.

A deep dive into Monarch Collective, another investment firm focused specifically on women’s sports. The firm, which was co-founded by Kara Nortman, has amassed stakes in three NWSL teams and recently raised an additional $50 million in capital, which brings its debut fund to $200 million. It’s now eyeing opportunities in the WNBA and European soccer — a report last week alleged the firm was in discussions to take a stake in Chelsea’s women’s team.

Speaking of Chelsea, the team just signed a record $1.1 million transfer deal for San Diego Wave player Naomi Girma. Lyon also reportedly came to the table with a $1 million offer.

The Athletic examines the sustainability of Unrivaled.

“At the end of the day, the product needs to be great for fans to continue to want to watch it,” said Alex Bazzell, the league’s president to The Athletic. “You can capture people’s attention, but how do you keep people’s attention? It’s done through the most competitive product possible, which is really what we’re adamant on, day in and day out.”

Image Source: Photo by Pixabay